Two-sided market

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Two-sided markets, also called two-sided networks, are economic platforms having two distinct user groups that provide each other with network benefits. The organization that creates value primarily by enabling direct interactions between two (or more) distinct types of affiliated customers is called a multi-sided platform (MSP).[1]

Two-sided networks can be found in many industries, sharing the space with traditional product and service offerings. Example markets include credit cards (composed of cardholders and merchants); HMOs (patients and doctors); operating systems (end-users and developers); yellow pages (advertisers and consumers); video-game consoles (gamers and game developers); recruitment sites (job seekers and recruiters); search engines (advertisers and users); and communication networks, such as the Internet. Examples of well known companies employing two-sided markets include such organizations as American Express (credit cards), eBay (marketplace), Taobao(marketplace in China), Facebook (social medium), Mall of America (shopping mall), Match.com (dating platform), Monster.com (recruitment platform), Sony (game consoles), Google (search engine) and others.

Benefits to each group exhibit demand economies of scale. Consumers, for example, prefer credit cards honored by more merchants, while merchants prefer cards carried by more consumers. Two-sided markets are particularly useful for analyzing the chicken-and-egg problem of standards battles, such as the competition between VHS and Beta. They are also useful in explaining many free pricing or "freemium" strategies where one user group gets free use of the platform in order to attract the other user group.[2][3][4][5][6]

Contents

[hide]Overview[edit]

Two-sided markets represent a refinement of the concept of network effects. There are both same-side and cross-side network effects. Each network effect can be either positive or negative. An example of a positive same-side network effect is end-user PDF sharing or player-to-player contact in PlayStation 3; a negative same-side network effect appears when there is competition between suppliers in an online auction market or competition for dates on Match.com. The concept of network effects were conceived independently by Geoffrey Parker and Van Alstyne (2000,2000, 2005) to explain behavior in software markets and by Rochet & Tirole[7] to explain behavior in credit card markets. The first known peer-reviewed paper on interdependent demands was published in 2000.

Multi-sided platforms exist because there is a need of intermediary in order to match both parts of the platform in a more efficient way. Indeed, this intermediary will minimize the overall cost, for instance, by avoiding duplication, or by minimizing transaction costs. This intermediary will make possible exchanges that would not occur without them and create value for both sides. Two-sided platforms, by playing an intermediary role, produce certain value for both users (parties) that are interconnected through it, and therefore those sides (parties) may both be evaluated as customers (unlike in the traditional seller-buyer dichotomy).

Structural characteristics[edit]

A two-sided network typically has two distinct user groups. Members of at least one group exhibit a preference regarding the number of users in the other group; these are called cross-side network effects. Each group’s members may also have preferences regarding the number of users in their own group; these are called same-side network effects. Cross-side network effects are usually positive, but can be negative (as with consumer reactions to advertising). Same-side network effects may be either positive (e.g., the benefit from swapping video games with more peers) or negative (e.g., the desire to exclude direct rivals from an online business-to-business marketplace).

For example, in marketplaces such as eBay or Taobao,[8] buyers and sellers are the two groups. Buyers prefer a large number of sellers, and, meanwhile, sellers prefer a large number of buyers, such that the members in one group can easily find their trading partners from the other group. Therefore, the cross-side network effect is positive. On the other hand, a large number of sellers mean severe competition among sellers. Therefore, the same-side network effect is negative.[8]

Figure 1 depicts these relationships.

Figure 1: Cross-Side and Same-Side Network Effects in a Two-Sided Network.[9]

Neither cross-side network effects nor same-side network effects are sufficient for an organization to be a MSP. Examining traditional supermarkets, it is clear that shoppers prefer higher number of suppliers and bigger variety of goods, while suppliers value higher number of buyers. Nevertheless, a supermarket does not qualify as an MSP because it does not enable direct contact between shoppers and suppliers. On the other hand, such network effects are not required for a firm to be seen as an MSP. One example is the situation in which niche event organizers implement a ticketing service managed by a small on-line ticket provider in their websites. Consumers affiliate with the on-line ticket provider only when they go to the website to buy the ticket. However, cross-side network effects and same-side network effects are common in MSPs.[10]

In two-sided networks, users on each side typically require very different functionality from their common platform. In credit card networks, for example, consumers require a unique account, a plastic card, access to phone-based customer service, a monthly bill, etc. Merchants require terminals for authorizing transactions, procedures for submitting charges and receiving payment, “signage” (decals that show the card is accepted), etc. Given these different requirements, platform providers may specialize in serving users on just one side of a two-sided network. A key feature of two-sided markets is the novel pricing strategies and business models they employ. In order to attract one group of users, the network sponsor may subsidize the other group of users. Historically, for example, Adobe’s portable document format (PDF) did not succeed until Adobe priced the PDF reader at zero, substantially increasing sales of PDF writers.

In the operating systems market for home computers, created in the early 1980s with the introduction of the Macintosh and IBM PC, Microsoft decided to steeply discount the systems developer toolkit (SDKs) for its operating system, relative to Apple pricing at that time, lowering the barrier to entry to the home computer market for software businesses.[citation needed] This resulted in a big increase in the number of applications being developed for home computers, with the Microsoft Windows/IBM PC being the operating system/computer type combination of choice for both software businesses and software users.

Competition in Two-Sided Networks[edit]

Because of network effects, successful platforms enjoy increasing returns to scale. Users will pay more for access to a bigger network, so margins improve as user bases grow. This sets network platforms apart from most traditional manufacturing and service businesses. In traditional businesses, growth beyond some point usually leads to diminishing returns: Acquiring new customers becomes harder as fewer people, not more, find the firm’s value proposition appealing.

Fueled by the promise of increasing returns, competition in two-sided network industries can be fierce. Platform leaders can leverage their higher margins to invest more in R&D or lower their prices, driving out weaker rivals. As a result, mature two-sided network industries are usually dominated by a handful of large platforms, as is the case in the credit card industry. In extreme situations, such as PC operating systems, a single company emerges as the winner, taking almost all of the market.[11]

Pricing in Two-Sided Networks[edit]

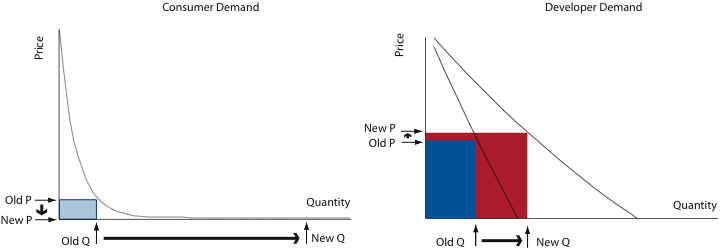

Platform managers must choose the right price to charge each group in a two-sided network and ignoring network effects can lead to mistakes. In Figure 2 below, pricing without taking network effects into account means finding prices that maximize the areas of the two blue rectangles. Adobe initially used this approach when it launched PDF and charged for both reader and writer software.[12]

Figure 2–Traditional pricing logic seeks the biggest revenue rectangle (price × quantity) under each demand curve.[13]

In two-sided networks, such pricing logic can be misguided. If firms account for the fact that adoption on one side of the network drives adoption on the other side, they can do better. Demand curves are not fixed: with positive cross-side network effects, demand curves shift outward in response to growth in the user base on the network's other side. When Adobe changed its pricing strategy and made its reader software freely available, its managers uncovered a key rule of two-sided network pricing. They subsidized the more price sensitive side, and charged the side whose demand increased more strongly in response to growth on the other side. As illustrated in Figure 3, giving consumers a free reader created demand for the document writer, the network's "money side."

Figure 3–So long as the revenue gained (red box) exceeds the revenue lost (light blue box), a discounting strategy is profitable. The subsidy largely changes network size.[13]

Similarly, gaming manufacturers very often subsidize the gamers and sell their consoles at substantial loses (e.g. Sony's PS3 lost $250 per unit sold [14])in order to penetrate the market and receive royalties of software sold for their gaming console.

On the other hand, even though two-sided pricing strategies generally increase total platform profits compared to traditional one-sided strategies, the actual end value of the two-sided pricing strategy is contingent on market characteristics and may not offset the costs of implementation. For example, profits of an application provider increase with the implementation of a two-sided pricing strategy of the platform provider only if the application is subsidized by the provider.[15] Platform providers should also be more cautious when the giveaway product has appreciable unit costs, as with tangible goods. Free-PC incurred $80M in losses in 1999 when it decided to give away computers and Internet access at no cost to consumers who agreed to view Internet-delivered ads that could not be minimized or hidden. Unfortunately, willingness to pay does not materialize on the money side, as few marketers were eager to target consumers who were so cost conscious.[16]

Strategic issues[edit]

If building a bigger network is one reason to subsidize adoption, then stimulating value adding innovations is the other.[17] Consider, for example, the value of an operating system with no applications. While Apple initially tried to charge both sides of the market, like Adobe did in Figure 2, Microsoft uncovered a second pricing rule: subsidize those who add platform value. In this context, consumers, not developers are the money side.

Figure 4–In this market, consumers care more about access to critical features. The main effect of a subsidy is to change network value.[13]

Which market represents the money side and which market represents the subsidy side depends on this critical tradeoff: increasing network size versus growing network value. The size rule lets you increase adoption more while the value rule lets you increase price more.

Although recently developed in terms of economic theory, two-sided networks help to explain many classic battles, for example, Beta vs. VHS, Mac vs. Windows, CBS vs. RCA in color TV, American Express vs. Visa, and more recently Blu-ray vs. HD DVD.

In the case of color TV, CBS and RCA offered rival formats but initially neither gained market traction. Viewers had little reason to buy expensive color TVs in the absence of color programming. Likewise, broadcasters had little reason to develop color programming when households lacked color TVs. RCA won the battle in two ways. It flooded the market with low cost black-and-white TVs incompatible with the CBS format but compatible with its own. Broadcasters then needed to use the RCA format to reach established viewers. RCA also subsidized Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color, which gave consumers reason to buy the new technology.

Multihoming[edit]

When two-sided markets contain more than one competing platform, the condition of users affiliating with more than one such platform is called multihoming. Instances arise, for example, when consumers carry credit cards from more than one banking network or they continue using computers based on two different operating systems. This condition implies an increase of “homing” costs, which comprise all the expenses network users incur in order to establish and maintain platform affiliation. These ongoing costs of platform affiliation should be distinguished from switching costs, which refer to the one time costs of terminating one network and adopting another.

Their significance in industry and antitrust law arises from the fact that the greater the multihoming costs, the greater is the tendency toward market concentration. Higher multihoming costs reduce user willingness to maintain affiliation with competing networks providing similar services.

Winner take all[edit]

Attracted by the prospects of large margins, platforms can try to compete to be the winner-take all in two-side markets with strong network effects. That means that one platform serves the mature networked market. Examples standard battles include VHS vs Betamax, Microsoft vs Netscape or the DVD market. Note that not all two-side markets with strong positive network effects are intended to be supplied by one platform. Markets must have high multi-homing costs and similar consumers’ needs.[11]

Even if the market is meant to be dominated by one platform, companies can choose cooperate together rather than competing to be the winner-take-it-all. For instance, DVD companies pooled their technologies creating the DVD format in 1995.[18]

In case of fighting companies will take stranding risk in the short term but in the long term companies can price according to monopoly theories. Consequently, winner-take all can be threatened by government intervention.

Threat of envelopment[edit]

Since frequently platforms have overlapping user bases, it is not uncommon for a platform to be "enveloped" by an adjacent provider.[19]

Usually, this occurs when a rival platform provides the same functionality of your platform as a part of a multiplatform bundles. If your money-side perceives that such multiplatform bundles delivers more value at a lower price, your stand-alone platform is in danger. If you cannot reduce price on the money-side or enhance your value proposition, you can try to change your business model or find a “bigger brother” to help you. The last option when facing envelopment is to resort to legal remedies, since antitrust law for two-sided networks is still in dispute. However, in many cases a stand-alone business facing envelopment has little choice but to sell out to the attacker or exit the field.[6]

See also[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ http://www.hbs.edu/research/pdf/12-024.pdf Andrei Hagiu and Julian Wright (2011). Multi-Sided Platforms, Harvard Working Paper 12-024.

- ^ http://ssrn.com/abstract=249585 Geoffrey Parker and Marshall Van Alstyne (2000) "Information Complements, Substitutes, and Strategic Product Design"

- ^ http://rje.org Bernard Caillaud and Bruno Jullien (2003). "Chicken & Egg: Competing Matchmakers". Rand Journal of Economics 34(2) 309–328.

- ^ http://idei.fr/doc/wp/2005/2sided_markets.pdf Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole (2005). [Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report]

- ^ http://ssrn.com/abstract=1177443 Geoffrey Parker and Marshall Van Alstyne (2005). ``Two-Sided Network Effects: A Theory of Information Product Design.” Management Science, Vol. 51, No. 10.

- ^ a b http://hbr.harvardbusiness.org/2006/10/strategies-for-two-sided-markets/ar/1 Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, and Marshall Van Alstyne (2006). [ "Strategies for Two-Sided Markets.” Harvard Business Review].

- ^ 2001, 2003

- ^ a b Chen, Jianqing; Ming Fan; Mingzhi Li (2015). "Advertising versus Brokerage Model for Online Trading Platforms". MIS Quarterly: forthcoming.

- ^ http://www.hbsp.com Eisenmann (2006), ``Managing Networked Businesses: Course Overview.”

- ^ http://www.hbs.edu/research/pdf/12-024.pdf Hagiu A., Wright J. "Multi-Sided Platforms" Harvard Working Paper 12-024.

- ^ a b http://hbr.org/2006/10/strategies-for-two-sided-markets/ar/1 Eisenmann T., Parker G., and Van Alstyne M.W. "Strategies for Two-Sided Markets" Article Preview, Harvard Business Review, October 2006

- ^ http://www.hbsp.com Tripsas (2000), "Adobe Systems, Inc.", Case 9-801-199.

- ^ a b c http://ssrn.com/abstract=1177443 Parker and Marshall Van Alstyne (2005), page 1498.

- ^ Kenji Hall, "The PlayStation 2 Still Rocks.

- ^ Economides, Nicholas; Katsamakas, Evangelos (July 2006). "Two-Sided Competition of Proprietary vs. Open Source Technology Platforms and the Implications for the Software Industry". Management Science 52 (7): 1057–1071.doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0549.

- ^ Thomas R. Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, Marshall W. Van Alstyne (2006). Strategies for Two-Sided Markets, Harvard Business Review.

- ^ J. Gregory Sidak, The Impact of Multisided Markets on the Debate over Optional Transactions for Enhanced Delivery over the Internet, 7 POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA Y REGULATORIA EN TELECOMUNICACIONES 94, 96 (2011).

- ^ Carl Shapiro, Hal R. Varian (1999). Art of Standards Wars (http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/shapiro/wars.pdf)

- ^ http://ssrn.com/abstract=1496336 Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, and Marshall Van Alstyne (2011). "Platform Envelopment.” Strategic Management Journal.

References[edit]

- Sangeet Paul Choudary (2013) "Platform Thinking" A Comprehensive Guide to Platform Business Models

- Geoffrey G Parker and Marshall Van Alstyne (2000). "Internetwork Externalities and Free Information Goods," Proceedings of the 2nd ACM conference on Electronic commerce; also available at SSRN: Information Complements, Substitutes, and Strategic Product Design

- Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole (2001). Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets.

- Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole (2003). Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(4): 990-1029.

- Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole (2005). Two-Sided Markets: A Progress Report

- Bernard Caillaud and Bruno Jullien (2003). ``Chicken & Egg: Competing Matchmakers. » Rand Journal of Economics 34(2) 309–328.

- Geoffrey Parker and Marshall Van Alstyne (2005). ``Two-Sided Network Effects: A Theory of Information Product Design.” Management Science, Vol. 51, No. 10.

- Thomas Eisenmann (2006) ``Managing Networked Businesses: Course Overview.” Harvard Business Online

- Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, and Marshall Van Alstyne (2006). "Strategies for Two-Sided Markets.” Harvard Business Review.

- Mark Armstrong (2006). "Competition in two-sided markets"

- Book : Invisible Engines : How Software Platforms Drive Innovation and Transform Industries – David Evans, Andrei Hagiu, and Richard Schmalensee (2006). http://mitpress.mit.edu/catalog/item/default.asp?ttype=2&tid=10937

- Weyl, E. Glen (2010). "A Price Theory of Multi-sided Platforms". American Economic Review 100 (4): 1642–1672. doi:10.1257/aer.100.4.1642.

- Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, and Marshall Van Alstyne (2011). "Platform Envelopment.” Strategic Management Journal, Vol 32.

- Institut D'Economie Industrielle: Two-Sided Market Papers

No comments :

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.